In Conversation with Amalia Mesa-Bains: Interview V

“IN CONVERSATION WITH” IS A CONVERSATIONAL INTERVIEW SERIES WHERE WE SIT DOWN WITH CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS AND DISCUSS TOPICS THAT ARE IMPORTANT TO THEM.

(All conversations are recorded, and transcribed by BrassTuna.)

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity

Amalia Mesa Bains is an artist and cultural critic who has worked to define Chicano and Latino art in the United States and in Latin America. Mesa-Bains is best known for her large-scale installations and interpretations of traditional Chicano altars and ofrendas.

Her work explores Mexican American women's spiritual practices, addresses colonial and imperial histories, the recovery of cultural memory, and their roles in identity formation. She also uses aesthetic strategies to as ways to express experiences historically associated with Mexican American women and as sites for Chicana feminist reclamation.

Mesa-Bains was born in Santa Clara, CA.

(Biography from amaliamesabains.com)

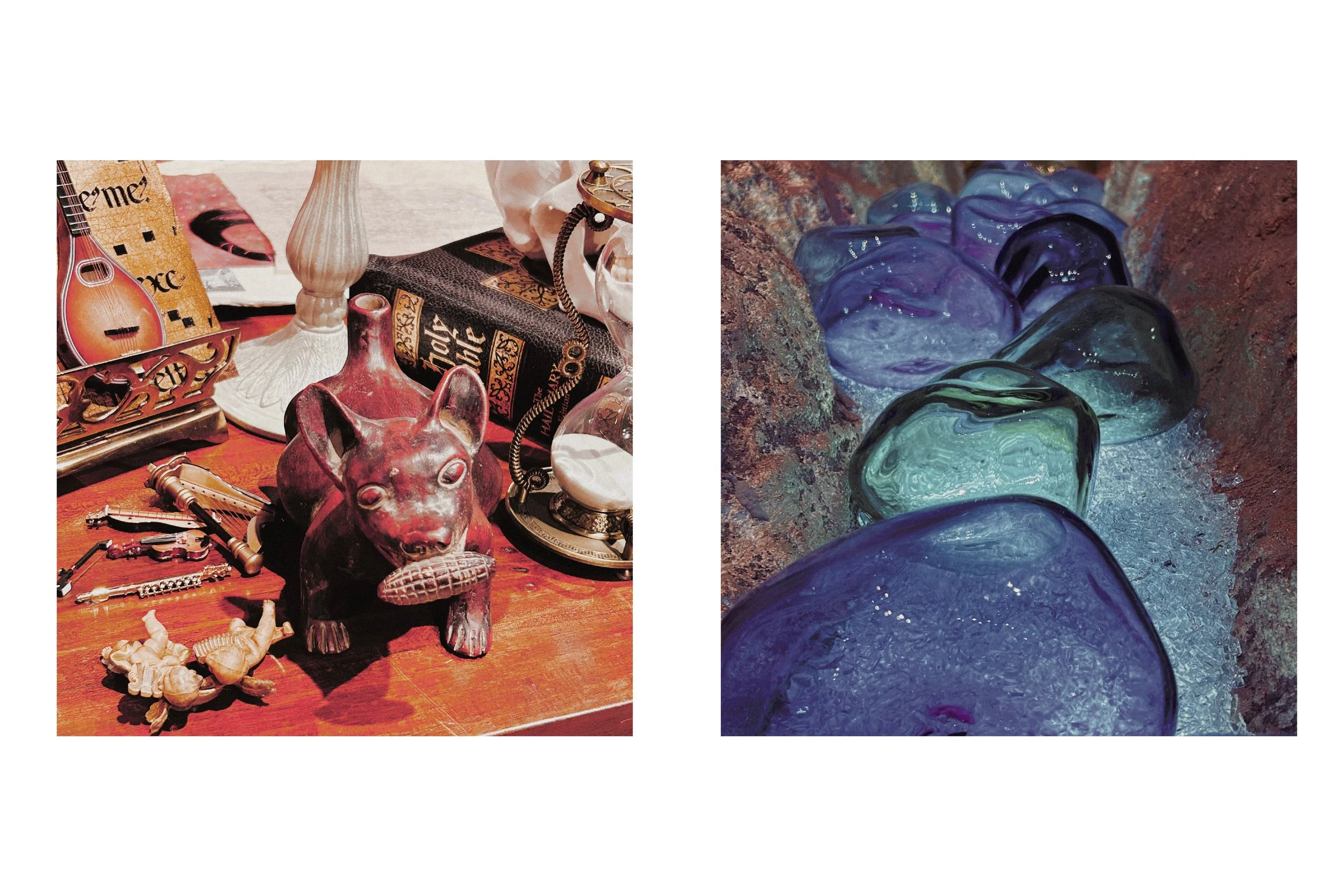

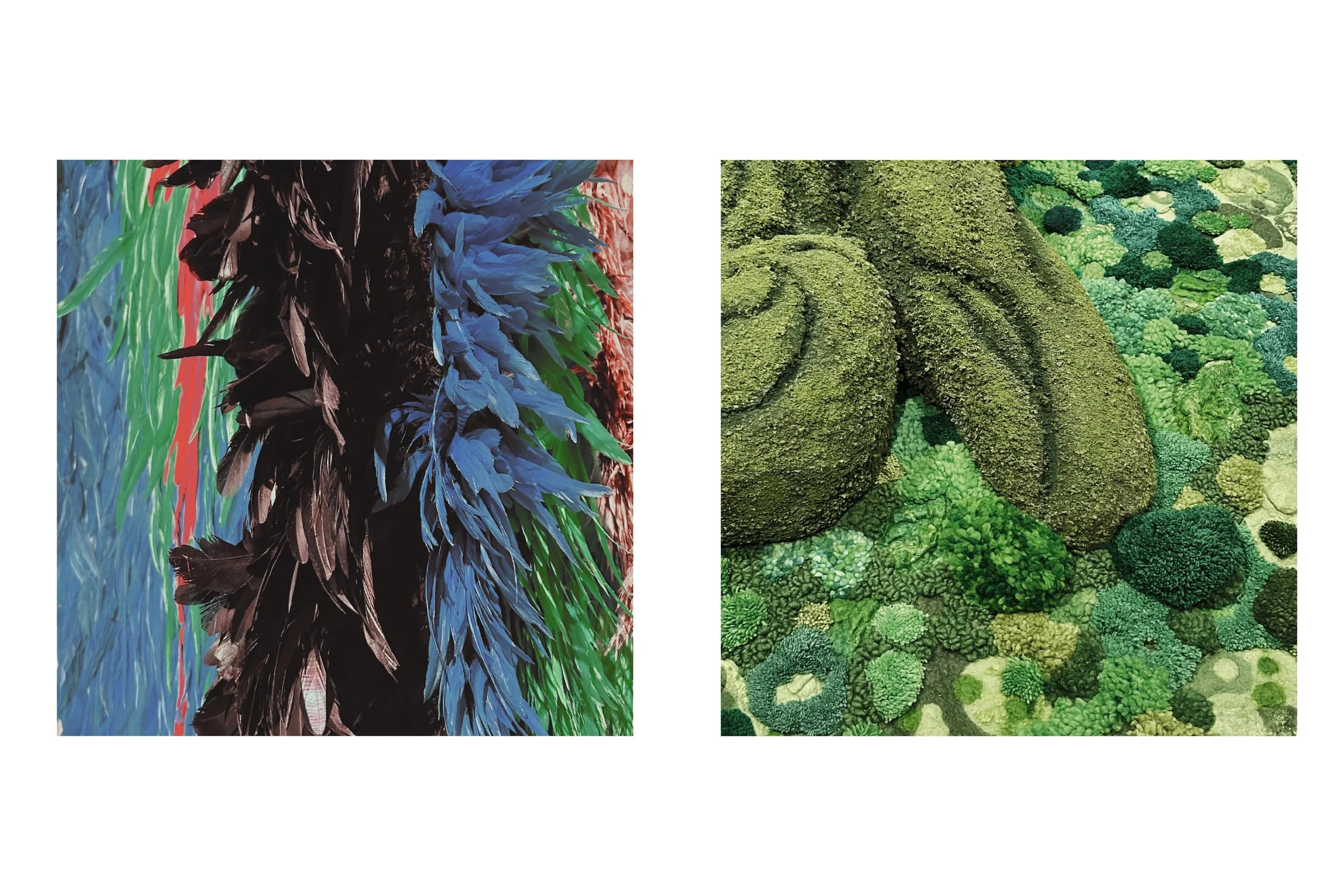

(Images captured by BrassTuna from “Archeology of Memory” Exhibition)

BrassTuna: Hello everyone, today I have the honor of speaking with artist Amalia Mesa-Bains. Amalia, thank you so much for joining me today. Would you mind telling our readers a bit about yourself?

A.M.B: “My name is Amalia Mesa-Bains, sometimes known as @dr_amalia_says on Instagram. I am an artist and a scholar and I have been a community activist for most of my adult life, and I’m very excited to be talking to Adam today, because I feel, as I’ve said many times ,,, that we are in a very long race, of relaying and passing the baton.

So each time I get a chance to talk with a younger person from the generations after me I feel excited.

You know I had a long career, over 50 years, and I’ve had many occupations, and I have a joke that I've severely over-employed, but I’m all in retirement now, and my work is getting more public recognition.

And what that means is that our community is getting more public recognition and one of the things that gives me joy about the work and things that I write about in terms of Chicano and ChicanX culture is really that we are educating people outside of our communities to value and understand us more.

We’ve had to deal with, at least in my lifetime, a lot of pejorative and negative ideas and we’re in a political climate where that’s coming back again.”

*CALL CUTS OUT*

BrassTuna: Sorry about that! Haha, Zoom apparently doesn’t want us to speak today. *haha*

Let’s pick up where we had left off. You were telling us just a bit about yourself, Amalia.

A.M.B: “My own background is a bit complicated in the sense that, I’m highly educated.

‘Overly educated’ some would say.

I have a master’s in psychology and a PhD, and my dissertation was a study of Chicana women artists and the influence of culture in their work and their personalities.

And prior to that, I had a master’s in public education, interdisciplinary studies, and a BA in painting.

So I’ve kind of moved in my own way. I don’t think I had a very direct pathway.

And a lot of it has to do with things that I had to deal with in my life, that made me interested in psychology and then later I realized that I would always be an artist.

So even when I had thought I might become a clinician in the end, I stayed in the public sector, going into higher ed, and starting a new program in public and visual arts, almost … almost 30 years ago at CAL State University of Monterrey Bay.

And I’ve maintained through all those years my art practice, my scholarly writing, and I think I’m probably one of the earliest to write about Chicana artists in particular.

Because no one else had a PhD, although mine wasn’t in art history, I had studied quite a few artists that were notable at the time, so I’ve continued to write for them.

So I’m sort of able to call it a polymath, I don’t know what you would call it ,,, simply a person that is very curious, and I guess I feel like you have to be able to respond to the opportunities that come to you. And that in all of it, whatever the dimension of profession I might be seen as having, they are all aimed at issues of culture, education, and political struggle.

Those are really things that keep me going on what I do. And I’m in a resurgence now, I don’t quite understand it, because I am going to be 81 in about another week, so I am very grateful that there is still a place for my work.

And I think its really lovely that younger people like yourself are interested in it.”

(Images captured by BrassTuna from “Archeology of Memory” Exhibition)

BrassTuna: I was lucky enough to meet you in person, and show my appreciation for your work, though we didn’t have a lot of time then to speak.

Since then, I’ve done a lot of research on your installation pieces and work, so I won’t speak too much about specific pieces for this interview, but instead, I want to focus more so on you and your process as an artist.

When looking back on your life were there any moments you felt you needed to assimilate into “American Culture,” to gain respect, representation, or space?

A.M.B: “Actually, probably from the minute I started going to public school. I felt the pressure to adapt in some way. My parents both had come when they were quite young. My father was born during the Mexican Revolution, so he came around 1916 or 17, with his mother, her three brothers, and his one sibling.

So they had no papers, because they had no port of entry, because in the years of the revolution, people were just flooding out by the thousands.

My mother on the other hand, who is about 7 or 8 years younger than my father, came across in the early 20’s. She was around 4 or 5. She came across with her mother to clean houses on the American side, once again no port of entry, no papers.

So I grew up in an undocumented community, which I think included a lot of my relatives. So I think that was one of the elements that maybe made it, I guess more advisable for me to be ‘more American,’ and ‘less Mexican.’

So my mother and father understood that, because they had already gone through living in the US, I think he was 27 when they married and she was probably 20. So they already had their fair share of discrimination, really badly. We are talking like the 1930’s and 40’s, so pretty bad.

So they had made up their mind that we would not speak Spanish, so we spoke English in the home. Although my grandmother only spoke Spanish, and I spent much of my time with her.

We all lived in the same two or three-block area. All of my relatives. So I would drop by with my cousin to see my grandmother, then we’d walk over to my house, to be with my mom. And so I learned from my grandmother that I understood Spanish perfectly. I read and write it, but I’m not a native Spanish speaker because ,,, I don’t think my parents forced us not to, they just always spoke to us in English because they didn’t want us to have an accent and didn’t want us to be discriminated against.

First of all, we were quite tall, my brother and I, for our generation. I was born in ’43. So I went into the public schools in 1948. Which was literally a year or so after the Mendez Decision, which was much earlier than Brown vs the board of Education. And desegregated Mexican segregation in the southwest.

So prior to my schooling, it was segregated. So I was in the first generation that went to schools with white children, and I think, it felt not really safe for my parents, and everything was properly kosher. Shoes shined, hair fixed, you know, not a thing out of place, so there could be no ‘bad experience for us.’ That didn’t stop it but it did make it easier.

I did know, almost from the beginning, that I had to make this adaptation, and high school was the worst, because I was very popular, and if you were popular then your options were “whiteness” and I don’t think I came out of that until about my first year in junior college.

And then I was angry and stayed angry for about 20 more years. *haha*

Thinking about ‘why did I compromise myself in that way? Why did I avoid my own cultural background?’

So people in my generation were in the process of what we called cultural reclamation. And that was largely because, if we were in California, we had been forced in some ways to leave behind the cultural knowledge that our parents had passed on to us. I think in places like Texas, and Arizona, and Colorado, they’ve faced an even more rigorous discrimination, but it made them want to hold on.

So most of the Chicana’s that I met in the early movement were often Spanish-speaking, and had more sort of involvement with cultural material than I did. So my years in the early movement were ones of like reclamation and exploration.

So yes, I never did assimilate because I figured out pretty quickly that nothing I did, or how I dressed, or what I looked like was going to change the fact that sooner or later they are going to do or say something offensive, and I would have to learn to deal with it.

But it took me a long time.”

(Images captured by BrassTuna from “Archeology of Memory” Exhibition)

BrassTuna: For me as an artist, I’m in that space of reclamation, and I call it an “understanding and healing” of my inner child, who is still in me, and he isn’t going anywhere.

One of the biggest things is the fact that I don’t speak fluent Spanish, though all of my family does. There have been such devastating tolls that it has taken on me as a person, and that’s one of the biggest questions I wanted to ask you.

How a language can make or break you, from a cultural standpoint.

For me, I feel I’ve reached a place where I am making work that is reminiscent of Mexican culture and history, with of course my own style.

And sometimes I feel like I face this,,, question of “Is it cultural appropriation?”

Though for me this is the experience that I’ve lived, and that I know.

I’m just curious how or did language ever take a toll on you and your creation process?

A.M.B: “Well because I’m from an early generation, Mexican culture was quite available to me.

Because my Abuela, my Grand Tios, all of those people were all dominant Spanish speakers.

They knew all the music, you know ,,, the food, we lived a very Mexican life, and I would go out into the white world, and I would come back and tell them what happened and how it was.

But I have to say that I discovered that I had a kind of store of passive language, in other words, I understand Spanish completely because it’s sort of stored in me.

From my grandmother speaking to me, my cousins, and in some ways, Spanish is an intimate language to me.

It’s not a public language, it’s a language of love and of scolding… because, you know when you’re bad they would scold you in Spanish.… ‘aye que traviesa’ ….

You start to learn, Spanish as a language of love or punishment, and then later you realize that many of your ideas, really visual and cultural, come through language.

First of all, the Spanish language has an act of agency around inanimate objects.

And often, you don’t say “the plane landed,” or ‘the plane arrived,’ you actually act as if the plane did come to you.

So the Spanish language itself sets conceptual frameworks for you. And I think in my case the language especially, of cultural traditions was so rooted in me.

From my family, it accounts for why I make the work that I do. And also the other part of it is that whether it was Spanish or English, or a mixture of the two, my family was so paramount in my life.

And all my family, sort of experiences, brought me to the space that I came to as an art maker. I’m third third-generation artist, my grand Tios were carvers, my Tios were carvers. And I and my cousins all draw. So I associate my art skills and my ability to express myself, with my cultural legacy.

I don’t think of it as something that came from outside or something that I learned.

It was always in me.

And my parents were very supportive of it. My father especially, because in his family, as I said I was third generation, so it’s almost like they were waiting for it, like they were expecting me to. So my first easel I got when I was 7, and you know it must have cost them a bit of money, and my father used to go to the butcher stores and collect the end of the butcher paper rolls. This is when butcher shops, had that kind of pink paper.

And they would throw away the rolls but there would still be paper on it because it was crimped along the edges so it wasn’t good for them.

But he would take the rolls, cut them in squares, and put rocks on top of them to flatten them. And those were the first things I painted on. So I really do think that despite the fact that I didn’t maintain a language, in the most full form, it has led me in many ways to the ideas that I have of time and space, it’s led me to all of the cultural materials that I have integrated into my installations, and most particularly the idea of legacy.

And so that I’ve hunted down photographs of all of my elders, and my ancestors, and I keep them around, and always inserting them into works because it makes me feel like even though some of them I never knew, I feel like ,,, its something Walter Benjamin said like, “that the dead expected us, we have an agreement with them that can never be settled cheaply,” in other words, they expected us, they gave their lives, to build a future in which we would be able to the things that we can do.

And so our loyalty to them is part of that bargain. And so for that, I always honor my ancestors with their images.

Like in “The Curandera’s Botanica” my grandmother is watching above the medicine table, and I always felt like, you know she was a very strong woman, and many of my father’s abilities and mine really came from her.

She is my guardian figure, so it’s not directly language, but it’s language as the basis for ideas, concepts, cultural beliefs, and cultural practices. And that is always part of my make-up.”

(Images captured by BrassTuna from “Archeology of Memory” Exhibition)

BrassTuna: You know, I am in the very beginning chapters of my book, but hearing you say that,,, it kind of feels like some of the clouds in my mind are parting, and clearing away…

A.M.B: “And I’ll tell you this, this is something that I learned at the beginning.

Like you, I came into the movement and I didn’t speak Spanish well, and I was married to a black man, I wasn’t married to a Mexican man. I had not been a Gudalupana, I was not educated with Guadalupe because my mother had been abandoned as a young girl in a convent, and was raised by Italian nuns outside of Los Angeles.

So I knew about Virgin Mary but I did not have a connection to Guadalupe, except I used to see that image in my grandmother’s room.

So one of the things that I learned, and I felt ,,, maybe a little bit embarrassed or ashamed for a few years, thinking that I was late to the party or that I wasn’t good enough, because I didn’t have what everyone else had. Who came from Texas or further down in southern California, and then I realized as long as I worked toward the movement and for the movement, and kept my faith with my comadres and compadres, I was just as Chicano as anyone else. And that’s what you learn, Chicano is a state of mind.

It is your belief and your commitment.

That can mean anything. You can be mixed-race, you can be middle class, you can be English dominant. But if you have a Chicano or ChicanX heart, and by that I mean, commitment to your community, your culture, your family. Then you’re ChicanX, that’s it, you know. So you don’t have to answer that to anyone. You are what you are.

Once you make that decision, and you begin that work, that’s what it is.

It took me a few years, but I learned it.”

BrassTuna: Whether or not your work is meant to represent those ideas, it still comes across. That’s why I’ve felt such a strong connection to your work.

I feel like I need a gavel to hit it down and put those words into law haha.

(Images captured by BrassTuna from “Archeology of Memory” Exhibition)

BrassTuna: This next topic is more so about your artistic style and the use of the word rasquachismo. I was unfamiliar with the term, but I was familiar with the style and the aesthetic applied.

For anybody who doesn’t know what rasquachismo is, “Rasquachismo: is a theory developed by chicano scholar Tomas Ybarra-Frausto to describe ‘an underdog perspective, a view from los de abajo in working class chicano communities which uses elements of “hybridization, juxtaposition, and integration” as a means of empowerment and resistance.’”

I’m curious as to why this specific style comes across so strongly in your work, and how has rasquachismo impacted your view on art?

A.M.B: “Well, first of all, Tomas and I are pretty much peers. We were writing and we lived near each other, and he’s been my friend for 50+ years.

When you were young you would hear that term, but it was very pejorative.

‘Aye que rasquache…,’ like ‘he’s so low’ or like ‘she’s got a pin in her bra strap,’ or ‘his shoes are run down.’

And then you understood it also meant, that you could make the most from all the leftover stuff.

Because you didn’t have the good stuff. So I first saw it in my godmother who lived in Mountain View, and this is way before Silicon Valley or anything like that. And in Mountain View, there was a whole Mexican community. And she used to make yard shrines. They were called ‘capillas,’ which means ‘little chapel.’

And they were like mosaics sometimes, with broken plates, broken bottles, coffee cans which you can put the plants in.

So I first started seeing these but I didn’t know what they were or why they were, and then I finally figured it out.

And Tomas and I spent hours talking about rasquachismo, especially because he is a bit older than me, maybe 5 years. So he got to go to what they call Carpa [Carpa Garcia] which is the tent shows, and they didn’t have them in California or at least I was too young to have gone to it.

He would talk about the people who would perform in there, with these sort of clown faces, and these crazy patched-together clothes. And so rasquachismo was like a negative thing and this is very Chicano, because the word Chicano was a negative thing. So what we would do, is take a negative thing and make it positive by embracing it.

So when he first started writing about it, we were looking at people like David Avalos, or even Jose Montoya, and there really was not language yet for the women, and that’s why I wrote ‘Domesticana.’

Because I wanted to sort of make it more specific to women, and I made the observation, that women, because of the patriarchal nature of Mexican culture, and even Chicano culture, we are sort of captured, within a space of a home. As well as being captured in a space the society that didn’t allow them,,, very much space to be who they were.

So they often made what they made from leftover,,, like we used to make decorative objects with chili peppers, from the kitchen, and people would take old pieces of fabric or doilies, that their grandmothers crocheted, and turn them into other arts of work.

So that’s where domesticana came about. I first started looking at ofrendas, and also which were day of the dead offerings, and those were ephemeral and limited in time.

Then I began to look at the home alters, and how the home alters had this same excessive decoration.

And those are permanent and ongoing…

I used to go to a restaurant in San Francisco, ‘La Rondalla’

,,, actually, I was once an extra in a Louis Malle film. It was filmed inside La Rondalla, called ‘Crackers,’ ,,, it didn’t go very well ,,, the movie. *haha*

Anyway, I spent a lot of time at La Rondalla, and one of the things about Rondalla is that it was totally rasquache. Every holiday they decorated, but they never took down the decorations. Then the next holiday would go on top of it. So pretty soon you could barely get your way in the door.

And the ceiling was just covered with stuff. And I adored it and I thought, ‘That’s just so perfect.’

So there were several kind of dimensions, that highly influenced me at the beginning.

One, I had the role of helping to do the ofrendas at the Galleria, the Mexican museum, Social Public Art Research Center, Guadalupe Center, I mean all these places I would go, and work on the ofrendas, and also I began to take up the idea of a home alter as well.

And then I began to play with them, expanding them, doing them as vanities, turning them into different kinds of furniture, as simultaneously my own natural instinct for sort of adornment was very rasquache.

I never really thought to do it, it simply happened, because of the nature.

My mother used to say when I was a child, she said I was like a little blackbird. I would walk down the street and if there was anything shiny my eyes would just focus on it and I would go over and pick it up and stick it in my pocket.

And I still do that.

So I think that rasquachismo was, in many ways a defensive pose within a very poor community. And it was also an inventive and creative strategy. And I come from the third generation of inventors.

So there are two strands in my father’s family; Artists, and Inventors. And they are real inventors with patents and everything.

And others like my uncle Louis, who I did honor in an ofrenda at the San Francisco Museum of Art, many years ago, and that was my first show I did in a mainstream museum.

And he had died, and they were doing a posada show, so they asked me to come in and do a piece, you know to be with the posada exhibit.

And I picked him because he was an artist but he was also very creative ,,, he and my father raised English bulldogs, not pit bulls, English bulldogs. They bred them, they showed them at the big Golden Gate kennel club and all of that ,,, we are very strange Mexicans. *haha*

I don’t understand it but whatever ,,, and my uncle also would train his dogs to do tricks, so in order to be sure he could get them food and water if he wasn’t there he invented these little machines, you would have to look them up because they aren’t something commonly known. They are called R-U-B-E Goldberg machines, and Rube Goldberg machines were like cartoons in the newspaper.

They were about these fantastical little machines, that people made up. So in my uncle’s case, there might be a little step ladder, maybe two steps, and it would be leaned against some kind of a pole but would have some kind of ,,, something you could push against.

And then whatever you pushed against on that, maybe like a dog door, would loosen a ball that would roll down and hit the edge of a bowl, where there was a water source adjacent, and the water bowl would tip the water, and the water would spill into the bowl, and the dog would drink.

They were very very wild things, and I learned later that in many ways he invented his own Mexican version of the Rube Goldberg, and they were very rasquache. They were made of all these odd bits and parts.

Like I had another uncle, one of the ones who made artwork and he collected old pieces of metal. For example, he might find a seat off a bicycle and he would attach it to wheels on a tractor, or some other thing and he would have all these inventions of things you could ride around.

And they were like toys, and we all played with them, and we never realized till later that he didn’t buy them, he made them.

So for me, rasquachismo was a lifelong intervention in my family, and then later as a sort of Chicano strategy, and then later for me as a way of describing how women within our community broke the boundaries of that kind of container of the home ,,, made their way out into the world and made art that reflected back on that home.

So we, unlike white feminists, we are not going to toss away the ways our mothers and grandmothers lived, we weren’t going to toss away the things our fathers taught us and we weren’t going to toss away our sense of home in order to be liberated. We had to be liberated in a different way. So I've always thought that Chicana feminism does not coincide with white feminism, and in fact it is only now when they talk about intersectional feminism that we can really see what it was that we were after.

So our feminist icons were not Gloria Steinem, or anyone like that. They were people like Emma Tenayuca, who led the pecan strikes almost as a teenager in Texas, or Luisa Moreno, or Josefina Bright. And they were all labor activists. So our leaders were feminist labor activists because work and liberation were also part of social justice for us.”

(Images captured by BrassTuna from “Archeology of Memory” Exhibition)

BrassTuna: Well as we reach the end of our interview, Amalia. I wanted to do something a bit different.

To finish off I've gathered a few ‘speed round’ questions from a couple of people I know, and some that I work with.

A.M.B: “Ooo we’ll do a speed round, I like speed rounds” *haha*

BrassTuna: First question,

Are there any specific artists you’ve been strongly inspired by?

A.M.B: “Oh yes, Betye Saar, probably the most of anyone.

But also very much the work of Kiki Smith, and then my mentor Yolanda Garfias Woo, who is a back-strap loom weaver.”

BrassTuna: I’ll have to research some of those artists! Awesome, next question.

What is one piece of advice you would give to the up-and-coming generation of Latin American artists today?

A.M.B: “Make community, have solidarity. Find your way to all the complexities of your community. Don’t be bounded simply by Chicano or Latino, try to look at other people who are in that same struggle for justice and cultural expression.”

BrassTuna: And for our last question,

Who is your favorite musical artist, and what is your favorite color?

A.M.B: “Oh wow. I love the Earth colors, like reds, browns, and golds. I do not like blue, I’ve gone on the record for that.

Musical, well you know I used to love the Eagles and all that but really, Julio Iglesias stays with me forever and ever, I listen to him at least twice a week. I love Mexican music, I just do. I was raised with it, and also Frank Sinatra, and all that era of singers. Who sang beautiful lyrics, that I love.

I try to keep up with the new music, but I have to say it’s the oldies that I love.”

BrassTuna: Awesome.

Amalia, Thank you again for joining me today. It has been such an honor to talk with you one on one.

You can find Amalia Mesa-Bains on their Instagram (@dr_amalia_says) as well as their website www.amaliamesabains.com

(Stay up to date on future BrassTuna “In Conversation With” interviews by following us on Instagram)

This Interview is Part I of BrassTuna’s “August 2024” publication.

Check out Part II “Diabla en la Playa” on Instagram (@brasstuna) and new limited edition cyanotype postcards on sale now.